Golden Opportunity for Design Patentees to Obtain Broader Protection

by Perry Saidman

Design patentees have finally caught a break. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit in in re Maatita (No. 2017-2037, August 20, 2018) held that a single plan view of the bottom of a shoe satisfies the enablement and definiteness requirements of 35 U.S.C. § 112. This was the finding despite the fact – clearly recognized by the court – that the three-dimensional nature of the actual shoe bottom could not be determined from the sole drawing, i.e., many different 3D possibilities were covered by the design claim.

“…. [T]he fact that shoe bottoms can have three-dimensional aspects does not change the fact that their ornamental design is capable of being disclosed and judged from a two-dimensional plan- or planar-view perspective – and that Maatita’s two-dimensional drawing clearly demonstrates the perspective from which the shoe bottom should be viewed.

Slip op. at 13.

As favorable as the holding is, the path that the court took to get there was a bit Byzantine.

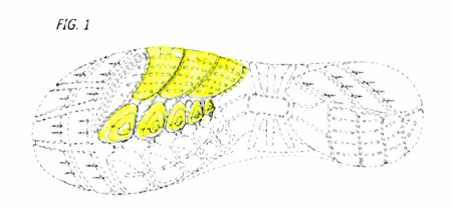

Maatita’s claimed design consists of a single figure:

The only portions of the design that are claimed are in solid lines in the middle of the forefoot, highlighted here for convenience. The rest of the design is in broken lines, i.e., unclaimed.

The Federal Circuit relied on a 1902 utility patent case from the Supreme Court to describe the purpose behind Section 112:

The purpose of Section 112’s definiteness requirement … is to ensure that the disclosure is clear enough to give potential competitors (who are skilled in the art) notice of what design is claimed – and therefore what would infringe.

Carnegie Steel Co. v Cambria Iron Co., 185 U.S. 403, 437 (1902).

Id. at 9

The court used that stated purpose to then connect the standard for indefiniteness to the standard for infringement:

In the design patent context, one skilled in the art would look to the perspective of the ordinary observer since that is the perspective from which infringement is judged.

Id.

These mental gymnastics – including a citation to the notorious and roundly criticized International Seaway case – resulted in the following statement from the court on how to determine whether the claim of a design patent satisfies § 112:

[A] design patent is indefinite under § 112 if one skilled in the art, viewing the design as would an ordinary observer, would not understand the scope of the design with reasonable certainty based on the claim and visual disclosure.

Id. at 10.

In approving the applicant’s single plan view, the court noted:

A potential infringer is not left in doubt as to how to determine infringement. In this case, Maatita’s decision not to disclose all possible depth choices would not preclude an ordinary obsever from understanding the claimed design, since the design is capable of being understood from the two-dimensional, plan- or planar-view perspective shown in the drawing.

Id. at 13.

Simply stated, the court said that as long as one can make comparisons for infringement purposes based on the provided, two-dimensional drawing, the claim would meet the enablement and definiteness requirements of §112.

SDLG Comment:

According to this case, a designer skilled in the art (a legal fiction) must view the claimed design as an ordinary observer (another legal fiction) who would then need to determine whether the scope of the design is understood with reasonable certainty. Since a court – or in rare cases a jury – is actually doing the viewing, it will be interesting to see in practice how it jumps through these two fictional hoops. If the facts of the Maatita case are any guide, it is hard to imagine a single plan view design claim that cannot be understood with reasonable certainty.

This case opens up a whole new opportunity for design patentees to broadly claim their designs with but a single plan view, and not worry too much about satisfying the disclosure and enablement requirements of §112. Foreign applicants, especially, should benefit, since in the past the drawing requirements abroad were far less onerous than US drawing requirements. Previously, many foreign-origin design applications claiming priority ran into § 112 trouble in the USPTO due to the strict disclosure and enablement requirements imposed by USPTO design examiners. Although one cannot predict how the USPTO will now treat disclosure and enablement issues based on the Maatita decision, there should be a considerable relaxing of the formerly strict interpretation of the requirements of § 112. A well-crafted single view design application would presumably be able to protect what the applicant regards as the important part of the design regardless of how the three-dimensional product (of the applicant or the infringer) actually looks. A side benefit is potential cost savings in design patent drawings, since only a single view need be submitted.